The national debate over an Indiana religious-liberties law seen as anti-gay has drawn the entire field of Republican presidential contenders into the divisive culture wars, which badly damaged Mitt Romney in 2012 and which GOP leaders eagerly sought to avoid in the 2016 race.

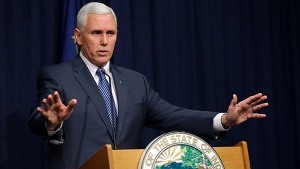

Most top Republican presidential hopefuls this week have moved in lock step, and without pause, to support Indiana Gov. Mike Pence (R) and his Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which has prompted protests and national calls for boycotts by major corporations.

Pence seemed surprised by the backlash and has had some difficulty explaining his position. Other potential 2016 candidates have leapt to his defense, and some, like Florida Sen. Marco Rubio, went further than the Indiana governor.

Supporters say Indiana’s law is similar to the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act passed in 1993.

As is often the case in controversies, however, the facts have become muddled and conflated. So what are the facts? How are the two laws different? And how have politics on both sides shaped the response?

“Now you have a situation in which there’s a much steeper price for Republican lawmakers who take action to motivate their base on this issue,” says John Ullyot, a GOP strategist and managing director of High Lantern Group, a management consulting firm in Washington. “Any position that is seen as intolerant for LGBT [lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender] people – now that’s a turn off for many swing voters, for many in the center, and for many moderate Republicans.”

The federal version of the RFRA passed as a bipartisan piece of legislation in 1993 and was signed by then President Clinton. But the new Indiana law, as well as a bill passed Tuesday by Arkansas, have unleashed a torrent of criticism, particularly from those who believe key differences between those states’ versions and the federal one could permit discrimination against same-sex couples in religiously-owned retail shops.

Another hypothetical outcome of the New Mexico case involving the lesbian couple and the photography studio. If New Mexico had the same religious freedom law as Indiana, the case would have gone to trial. But New Mexico has a nondiscrimination law that protects the LGBT community, it and it would have provided a strong counter-argument to the religious freedom claim.

Another hypothetical outcome of the New Mexico case involving the lesbian couple and the photography studio. If New Mexico had the same religious freedom law as Indiana, the case would have gone to trial. But New Mexico has a nondiscrimination law that protects the LGBT community, it and it would have provided a strong counter-argument to the religious freedom claim.

In Indiana, that protection would be lacking. (It gets more complicated when some local governments, like the city of Indianapolis, do have nondiscrimination ordinances).

For this reason, Holbrook suggests that a “fix” for the Indiana law would be the passage of a nondiscrimination law. Or, at the very least, an exception written into the religious freedom bill that protects from such discrimination.